EU AI Act delay reshapes risk for enterprise across Europe

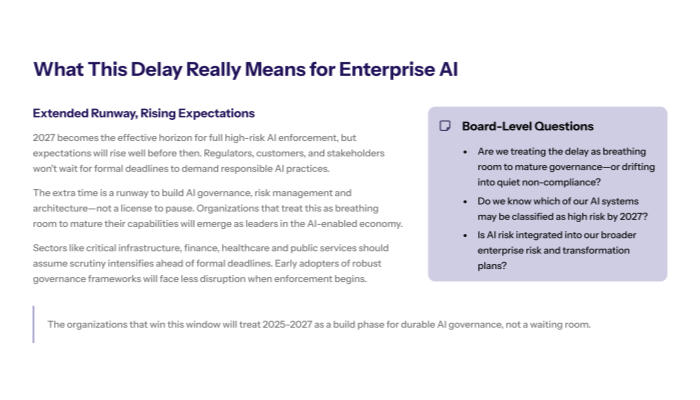

The European Union has decided to postpone enforcement of the most demanding “high risk” provisions of the AI Act until 2027, softening the near-term compliance cliff that many organisations were preparing for. On paper, this is a reprieve: regulators are giving businesses more time to adapt, document and redesign their AI systems. In practice, the delay raises a harder question for executives and boards: how do you plan in an environment where regulatory direction is clear, but exact obligations keep sliding? The answer will separate organisations that quietly drift into non-compliance from those that treat the next two years as a runway to build durable AI governance.

Key takeaways

-

The EU is delaying core high risk AI Act rules until 2027, easing immediate pressure but extending a period of regulatory uncertainty.

-

Enterprises should treat the delay as extra time to invest in AI governance, risk management and architecture, not as permission to pause.

-

Sector-specific impacts will vary, but any organisation with critical infrastructure, financial services, healthcare or public sector contracts will face higher expectations before the formal deadlines arrive.

What the EU AI Act delay actually changes

The AI Act was designed as a tiered framework, with stricter obligations for systems deemed “high risk” because of their impact on safety, rights or critical services. The decision to push key provisions to 2027 does not alter that basic structure. Instead, it changes when different obligations will bite, and how much time organisations have to translate a dense legal text into actual processes and controls.

Under the revised timeline, certain transparency, documentation and conformity-assessment requirements for high risk systems are expected to enter into force later than originally planned. That means fewer legally binding obligations in 2026, but more work for in-house legal, compliance and engineering teams in the years leading up to 2027.

High risk systems and phased enforcement

The high risk category includes applications such as credit scoring, recruitment algorithms, biometric identification in public spaces, medical decision support and systems used in critical infrastructure. These are precisely the systems that depend on robust data pipelines, reliable models and well-governed software development life cycles.

Many of the obligations for such systems are already understood:

-

extensive technical documentation and data governance

-

risk management and incident handling procedures

-

human oversight mechanisms

-

monitoring and post-deployment logging

-

conformity assessment and, in some cases, CE marking

What changes with the delay is not the content of the obligations but the enforcement calendar. The EU is effectively admitting that both regulators and industry need more time to build capacity. That does not mean scrutiny disappears. Voluntary codes, supervisory guidance and soft-law expectations will increasingly fill the gap before formal deadlines.

Why 2027 became the new political compromise

Pushing high risk provisions to 2027 reflects a political compromise between multiple pressures: industry lobbyists warning about innovation flight, civil society groups arguing for stronger protections, and member states concerned about the cost and complexity of implementation.

The EU has already signalled in other debates that it can adjust timelines without abandoning objectives. Earlier reporting around attempts to soften aspects of the AI Act under pressure from large technology firms hinted at this balancing act. The current delay follows the same pattern: the destination remains the same, but the road is being made longer and more winding.

For enterprises, this means that betting on the AI Act being watered down to oblivion is a risky assumption. Direction of travel is stable; only timing is variable.

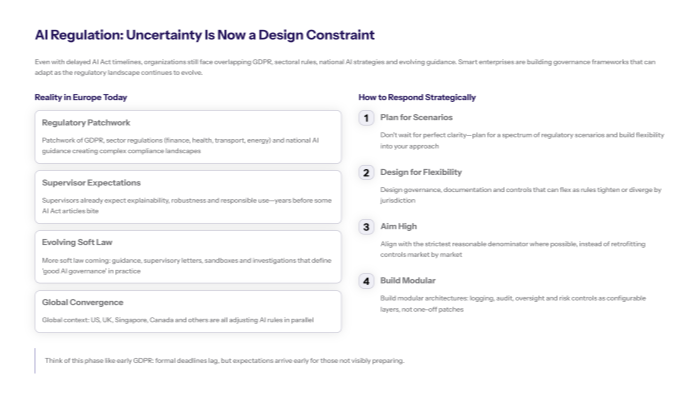

Regulatory uncertainty as a strategic variable

Regulatory uncertainty is now a permanent input to AI strategy, not a temporary irritant. The EU’s decision adds another example to a long list of shifting AI rules across jurisdictions, from US executive orders to national AI frameworks in the UK, Singapore or Canada.

The right response is not to wait for perfect clarity. Instead, organisations should plan for a range of plausible regulatory scenarios and ensure that their governance, documentation and architecture can flex as rules evolve.

Patchwork of national rules and soft law

Even with the AI Act delayed in part, European organisations still face overlapping requirements:

-

existing GDPR obligations governing personal data used in AI systems

-

sectoral rules in finance, healthcare, transport and energy

-

national AI strategies and sector guidance from regulators

-

emerging expectations from supervisors around explainability and robustness

Regulators will not sit idle until 2027. Expect more guidance, supervisory letters, sandbox schemes and investigations that indirectly define what “good AI governance” looks like in practice. For CIOs and CISOs, this environment resembles the early years of data protection enforcement after GDPR: formal deadlines late, expectations early.

The risk, as highlighted in independent analysis such as Gartner’s work on critical generative AI blind spots for CIOs , is that organisations underestimate the governance and operational work needed until problems become visible.

Impact on cross-border AI deployments

Multinationals deploying AI systems across regions must also consider how the EU AI Act fits with policies elsewhere. An AI system rolled out in Europe, the US and Asia may face different transparency and oversight expectations, even if the underlying model is the same.

With the EU timeline shifting, some organisations might be tempted to align instead with looser regimes. That is short-sighted. Aligning with the strictest common denominator often proves more efficient over time than retrofitting controls country by country.

From an architecture perspective, this makes modularity crucial: logging, audit trails, risk scoring, review workflows and human oversight should be implemented as configurable layers that can be tightened or relaxed based on jurisdiction, rather than hard-coded into each application.

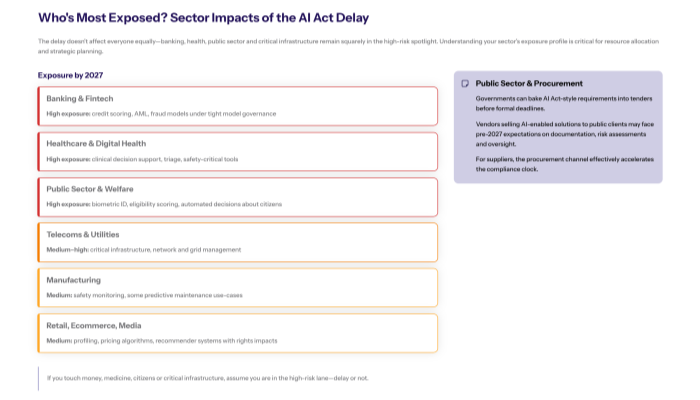

Sector-specific implications for high risk AI

Not every sector is equally exposed to the high risk provisions. Some industries will see mostly incremental adjustments; others will face structural changes in how AI-enabled processes are designed and monitored.

A comparative view by sector

Below is a simplified view of how the delay and future high risk enforcement are likely to affect different domains:

|

Sector |

Exposure to high risk rules |

Main impacts by 2027 |

|---|---|---|

|

Banking and fintech |

High |

Model governance, credit scoring, AML monitoring |

|

Healthcare |

High |

Clinical decision support, triage systems, safety |

|

Public sector |

High |

Biometric ID, welfare decisions, citizen scoring |

|

Manufacturing |

Medium |

Safety monitoring, predictive maintenance in some cases |

|

Retail and ecommerce |

Medium |

Customer profiling, pricing algorithms |

|

Media and advertising |

Medium |

Content recommendation, political advertising |

|

Telecom and utilities |

Medium to high |

Critical infrastructure, network management |

Enterprises in banking, insurance, digital health, social security and critical infrastructure should assume they are squarely within the AI Act’s core enforcement scope, even with the delay. Those in less regulated sectors should still expect increased scrutiny where algorithms affect fundamental rights or safety.

Public sector and procurement channels

One often overlooked vector is public procurement. Even before legal deadlines, governments may use tender requirements to impose AI Act-like standards on suppliers. That means vendors wanting to sell AI-enabled systems into public sector clients will likely face pre-2027 expectations around documentation, risk assessments and oversight.

For technology providers, this effectively accelerates the compliance timeline: you may need to meet AI Act-style requirements long before regulators formally enforce them.

What enterprises should do between now and 2027?

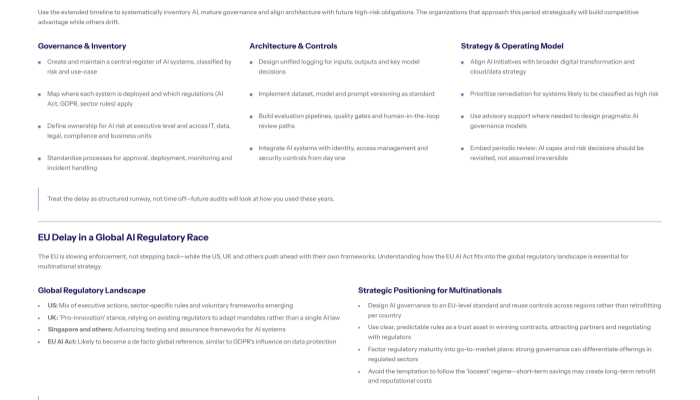

The additional time granted by the EU AI Act delay should be treated as a structured preparation window, not as margin to postpone action. Three areas deserve priority: governance, architecture and strategy.

Treat the delay as a runway, not a holiday

Organisations that start now will face a smoother path to compliance and a stronger position in future audits or investigations. A pragmatic roadmap might include:

-

inventorying AI systems and classifying them by risk and use-case

-

mapping where each system is deployed and which regulations apply

-

identifying gaps in documentation, logging, testing and oversight

-

prioritising remediation for systems likely to be deemed high risk

This is also a good moment to align AI strategy with broader digital transformation plans. AI cannot be governed in isolation; it interacts with cloud, data platforms, security controls and software development practices. Cognativ’s work on digital transformation strategy and AI at scale provides useful context for integrating governance into wider change programmes.

Build internal AI governance capabilities

Most organisations do not yet have mature AI governance structures. That must change. Central questions include:

-

Who owns AI risk at the executive level?

-

How are responsibilities split between IT, data, legal, compliance and business units?

-

What processes govern the approval, deployment and monitoring of AI systems?

-

How are incidents, near-misses and failures recorded and analysed?

Effective governance does not require an overbearing bureaucracy, but it does require clear lines of accountability, standardised processes and a traceable record of decisions. Many enterprises are now partnering with external specialists to design governance models that match their size and sector. Cognativ’s AI strategy consulting for growth and innovation explores these questions from a practical perspective.

Align architecture with future compliance

The AI Act’s high risk obligations will be much easier to meet if the underlying architecture is designed for observability and control. This includes:

-

unified logging for inputs, outputs and model decisions

-

versioning of datasets, models and prompts

-

standardised evaluation pipelines and quality gates

-

facilities for human-in-the-loop review and override

-

integration with identity and access management systems

Architectural decisions taken now will either make future compliance relatively straightforward, or painfully expensive. Building on an AI infrastructure that already foregrounds governance and observability is often more efficient than retrofitting compliance onto opaque models and fragmented data flows.

How this interacts with global AI regulation

The EU is not regulating in a vacuum. Organisations building AI systems must also track a growing web of global rules, guidelines and sectoral expectations.

US, UK and other frameworks

The United States is exploring a mix of executive actions, sector-specific rules and voluntary frameworks. The UK has opted for a “pro-innovation” approach, relying on regulators to adapt existing mandates rather than passing a single AI law. Other jurisdictions, such as Singapore, are moving ahead with testing and assurance frameworks for AI systems.

In practice, the EU AI Act will likely become a reference point even outside Europe, much as GDPR influenced global data protection norms. Multinationals may find it cheaper to design AI governance to a de facto EU standard, then reuse those controls elsewhere.

Competitive and geopolitical dimensions

There is a persistent narrative that stricter regulation will slow European innovation relative to less regulated regions. The more nuanced reality is that clear and predictable rules can be a competitive advantage if they reduce uncertainty and help build trust.

Enterprises that demonstrate strong governance and compliance may enjoy advantages in winning contracts, attracting partners and negotiating with regulators. Those that wait until 2027 to react may find themselves scrambling under supervisory pressure.

Conclusion

Delaying key high risk provisions of the EU AI Act until 2027 changes the tempo, not the direction, of AI regulation in Europe. Organisations now have more time to adapt, but they are also on notice: regulators expect serious progress in governance, documentation and architecture long before enforcement deadlines arrive. The winners will be those that use this interval to build resilient AI capabilities that can withstand scrutiny across jurisdictions.

For executive teams, the message is clear. Treat the AI Act not as a compliance chore that can be postponed, but as a catalyst to professionalise how your organisation builds, deploys and monitors AI. Those investments will pay off not only in regulatory resilience but also in trust, quality and long-term competitiveness.

If your organisation is starting to define or refine its AI roadmap, exploring structured support can accelerate the journey. Learn how Cognativ’s dedicated AI services and AI-first architecture expertise help enterprises align technology, governance and infrastructure with evolving regulation.

Stay ahead of AI policy shifts, infrastructure change and market signals. Follow What Goes On , Cognativ’s weekly tech digest, via the Cognativ AI and software insights blog for deeper coverage, context and executive-ready analysis.